Published on June 11, 2020

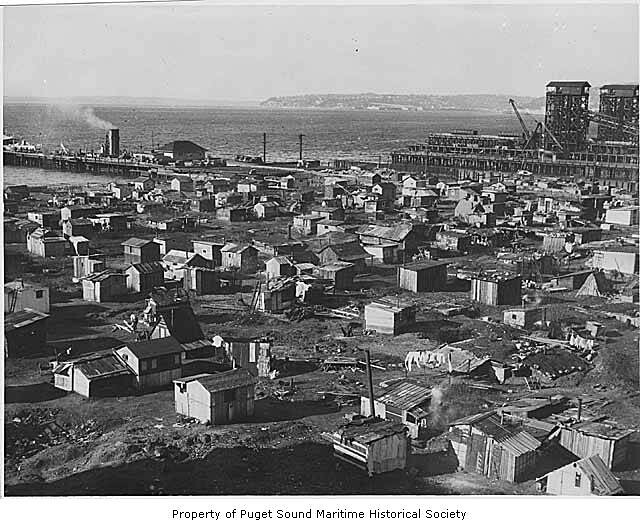

When the stock market crashed in fall of 1929, the road from joblessness to homelessness was short. Meager local relief programs and private charity weren’t up to the challenge of mass unemployment. As the Depression deepened and President Herbert Hoover resolutely opposed federal involvement in relief efforts, “Hoovervilles” sprang up around the country. Seattle’s largest shanty town, on the tide flats south of Pioneer Square, began in 1931 and lasted a full decade, at times housing more than a thousand people. According to Hooverville’s unofficial mayor, the lumberjack Jesse Jackson, its inhabitants were mainly older men. They were tradesmen, “seamen, lumberjacks, fishermen and miners,” most of them foreign-born.

While Seattle’s homeless were hammering together shacks and fashioning wood-burning stoves from automobile gas tanks, leftists were busy figuring out how to organize the unemployed.

In most U.S. cities, says University of Washington History professor James N. Gregory, “it was the Communist Party and the Unemployed Councils that were the most prominent organizers of unemployed politics.” But in Seattle, the group that gained traction was the homegrown Unemployed Citizens League, founded in summer 1931 by West Seattle socialists and labor activists associated with the Seattle Labor College.

The Unemployed Citizens League was built around cooperative self-help. “Out of people’s garages and neighborhoods they would exchange services, and they worked out various deals with nearby farmers, particularly Japanese growers in the Bainbridge area and over on the Eastside, to harvest crops that would otherwise go to waste,” explains Gregory. “They would share some labor and be paid in food, which then would be distributed in the neighborhood.”

Continue reading at Crosscut.

Originally written by Katie Wilson for Crosscut.