Published on January 7, 2022

People walking alone walk relatively quickly. A crowd walks slowly. But how does a crowd move when there is, say, a massive bull charging at them? To answer this, scientists analyzed the movement of a crowd of runners during the running of the bulls in Pamplona, Spain, in 2019.

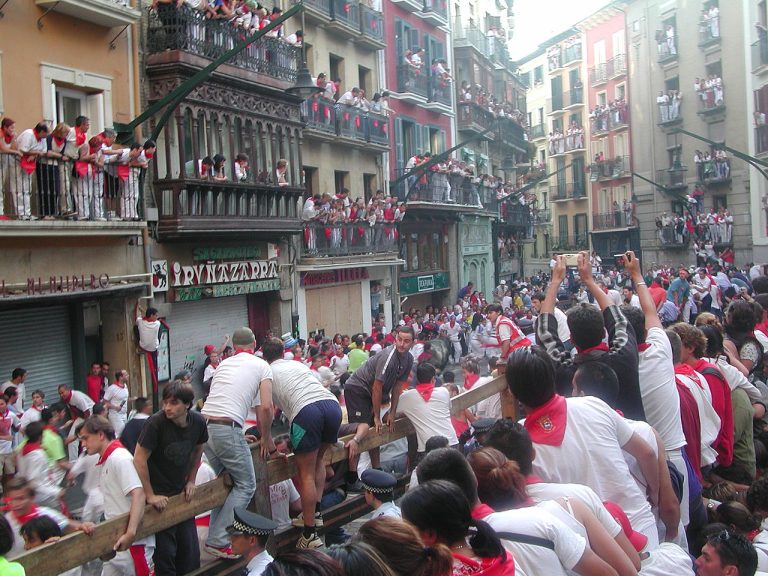

The San Fermín festival in Pamplona, Spain, hosts the world’s best-known running with bulls event. Every morning for a week each year, festival officials send six bulls charging down a set of narrow, blocked-off streets toward waiting crowds of people.

In 2019, pedestrian dynamics researcher Daniel Parisi, from the Technological Institute of Buenos Aires, attended the festival — though he was not running himself. Instead, Parisi was gathering data from a set of cameras roughly four or five stories above the route.

Pedestrian dynamics is the science of studying how crowds move and is useful for anyone designing or planning spaces like buildings or streets. Stadium exits that allow people to file out quickly without forming a human traffic jam may do so thanks to insights from pedestrian dynamics.

But there’s a gap in scientists’ knowledge. While scientists have a lot of data from crowds moving at walking speeds, when it comes to crowds running, there’s much less out there. It’s hard to predict when something will create a stampede of people in the real world. A running crowd can be dangerous if people start to trip each other.

By taking the videos and using software to tag and track the position of each runner, Parisi and his colleagues were able to explore whether scientists can use real-world events like this to look for insights.

And in doing so, they made two discoveries.

Firstly, Parisi and his team found that while the crowd could be at times fast or dense, there was a combination of speed and density that never occurred due to runners tripping each other and falling. “It’s intuitive,” said Parisi. “With restricted personal space, you can’t run very fast.”

Their second result, however, was unexpected. While it’s traditionally assumed that loose crowds move fast and dense crowds slow, Parisi found that as the bulls first approached the runners, for a short amount of time, the crowd became both denser and faster. “This is surprising and never was observed before,” said Parisi. He notes that this may be somewhat unique to the event’s particular circumstances — people starting relatively spaced out and stationary, only to be sent scrambling in extreme ways to avoid the bulls. The runners also know to expect the bulls, even if they don’t know precisely when they’ll show up.

The researchers’ paper, published this week in the journal PNAS, shows that by using the right technology, pedestrian dynamics researchers can indeed look to this kind of festival or extreme event for insight about crowds and their behavior, though more work needs to be done.

“I think that the methodology holds some promise,” said Rachel Berney, an urban design scholar at the University of Washington. She said she’d view the research as exploratory — it’s good to review any finding with other methods before relying on it — but that this type of research could provide insight for urban designers.

Originally written by James Gaines for Inside Science.