Published on July 6, 2021

After analyzing the human health risks of eating aquatic organisms from arsenic-contaminated urban lakes in the Puget Sound lowlands, UW researchers have a menu of concerns. Specifically, they found that consuming certain aquatic organisms in the lakes elevates cancer risk.

“The idea was to focus on organisms that people might eat, so we studied snails, crayfish and sunfish,” says UW Civil & Environmental Engineering associate professor Becca Neumann. “What we are seeing is elevated levels of arsenic in them.”

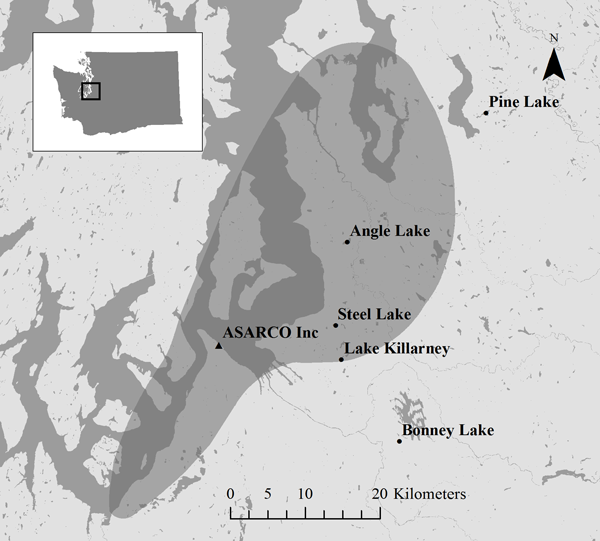

Four small public access lakes with varying levels of arsenic contamination and depth were selected for the study: shallow lakes Bonney Lake, Steel Lake and Lake Killarney, and Angle Lake, which is deeper than the others. All are located downwind of the former Tacoma-area ASARCO copper smelter, which pumped waste byproducts that contained arsenic and lead into the air for 96 years before ceasing operation in 1985.

Overall, the researchers found the shallow lakes had proportionately more arsenic in the sediments near the shore when compared to the deeper lake and that near-shore sediment and shallow water arsenic concentrations controlled the amount of arsenic in tissues of the snails, crayfish and sunfish. Lake Killarney, a shallow lake with the highest concentrations of arsenic in near-shore sediments, posed greatest human health risk. The study builds on research conducted two years ago, when the researchers discovered that the water of some shallow lakes contains surprising levels of arsenic, due to unique characteristics that facilitate the movement of arsenic from lakebed sediment up into the surface waters and near-shore areas where the aquatic food web resides.

Although it’s currently unknown how many people may be eating from the lakes, the researchers speculate that some populations may be fishing for subsistence reasons rather than sport. Many states, including Washington, don’t require a permit to harvest snails.

“The population we see out there fishing on a regular basis is more diverse than the nearby homeowner populations,” says Jim Gawel, associate professor of Environmental Chemistry and Engineering at UW Tacoma.

“There are fishermen who come out when they stock trout in the lakes, but there’s also a population that fishes throughout the year.”

Supported by UW’s Superfund Research program, the research team includes scientists from UW Civil & Environmental Engineering, UW School of Aquatic & Fishery Sciences, UW Tacoma Environmental Sciences, and Dartmouth College Department of Earth Sciences.

Originally written by Brooke Fisher for University of Washington Civil & Environmental Engineering.