Published on May 18, 2016

Britton Shepard is a Masters student in Landscape Architecture at the University of Washington, and will be graduating this June. He is currently wrapping up his thesis project, Site 1121: Field Notes, a public site exhibition of an abandoned lot that explored the history and identity of a landscape in an urban setting. The week-long installation took place in the U District at 1121 NE 45th St. March 21- 25, 2016, with support from the Washington State Employee’s Credit Union (WSECU), the owners of the vacant site. His thesis is an example of the unique urban research happening at UW every day.

(This article is part of a series of interviews exploring the work and perspectives of Urban@UW community members.) Urban@Uw: Britton, could you give us the one sentence version of your thesis. Britton: What happens when you open a gate on an abandoned site and invite people simply to explore what what is there, what does a shift in focus to experiencing a place as is rather than a new final product offer us? Urban@UW: Britton, you pursued a rather non-traditional approach to both your site and your thesis project. How did you decide on this abandoned lot? Britton: I had looked at other sites but this one kept emerging as the perfect opportunity: an abandoned site in a high density area by the University. I drove by this site, rode the bus past this site—I was frequently exposed to it in my everyday experiences. As I was working out my thinking regarding an urban field study, this seemingly abandoned and fenced off site in a busy area seemed like the best place to challenge assumptions about access and agency. Urban@UW: You mention ‘urban field study’—what do you mean by that? Britton: The approach was partially driven by ideas of a dig on an archeological site. The goal was to reveal: to minimize the introduction of new elements and curate what was already there. And I was deeply fascinated by slow, in-depth site work that engages people in the process instead of just a finished product.

Urban@UW: Tell us a little bit about the fence—it’s such a clear marker in a city that this is a place not to be trespassed, how did you negotiate that? Britton: The fence was very important. The status quo of a rectangle of fencing says, “Stay out—this is off limits.” Your access to space has already been decided for you. But I didn’t want to take the whole thing down—I believed that placing a few strong design elements—the boardwalks and work tables, moving existing things around and having humans in there would offer a way in—it would be an unusual form of agency. Urban@UW: How did you get access in the first place? How did you find an owner and get permission? Britton: King County Parcel Viewer was a great resource and eventually I found out that WSECU had purchased the site. I took a look at their branding and they seemed very people-oriented. Their work made them seem like a possible, relevant partner to be able to assist and even expand the project. So, I went to the branch across the street, walked up to a teller and asked if I could talk with someone about the possibility of a temporary installation at the site. They were open to the idea and passed my name on to Ann Flannigan, VP of Public Relations. Ann got in touch with me and I explained my idea and we discussed deadlines, purpose, and possibilities, particularly how I thought those lined up with their interests. They were interested in a neighborhood collaboration with the University, and even though it was a pretty unorthodox ask, they didn’t say no and we kept talking. Opening up a place like this meant that we had to be realistic about risk and insure safety. All told the process took 2-3 months from contact to full approval. But I have to say, I was never nervous. Things don’t always work out in life but this site was of high value to me and so we kept moving forward and eventually got there! I spent a lot of time prepping and exploring the site to make things legible and accessible. Urban@UW: How did the interactive part of the urban field study unfold? Britton: I approached fellow students in the Landscape Architecture department asking for their help as participants in the field study. I knew the success of the project depended on their being there! WSECU helped as well, promoting the project and setting up an employee volunteer schedule. Ultimately, we opened the gate, placed the boardwalks and signage to indicate something public was happening—and people just ended up coming in. Peoples’ response was a great experience to take part in.

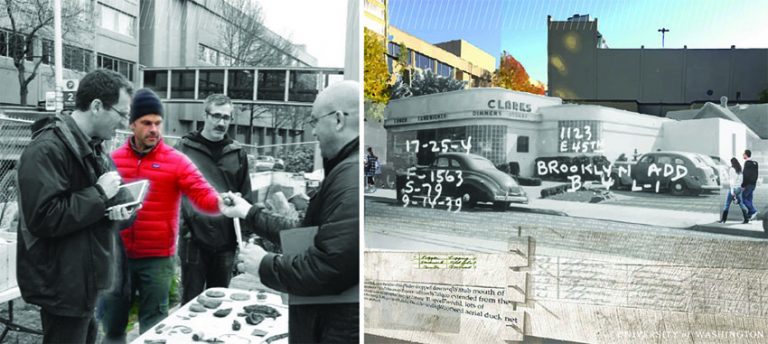

Urban@UW: What did you find? Britton: Well, there are so many of these sites in transition in Seattle—and as much as we build we rarely take the time to look at what’s already there. We found your normal detritus—needles, beer cans, trash—but we also found over 35 different plant species, tools, and railroad hardware. We created an artifacts table of found objects, converted the old foundation’s ruins into a gallery space, and put together a sofa out of sandbags. WSECU and UW volunteers also helped act as docents and diggers. It was sort of funny, frequently people who came to the site would ask, “Did you find anything valuable?” But we weren’t thinking in that way. When you take things like garbage, plants, or old hardware off the ground and arrange them they become something so much more. People start to see potential narratives. So, while we didn’t find anything of monetary value, people were finding valuable connections, experiences and questions once they came in and explored. Urban@UW: How do you see this project relating to broader urban issues? Britton: Exploring different ways of working with landscape demonstrated how energizing new ways of interacting with places can be. Curating a landscape by showing its process, history, and previous identities really “invited” activity into a place rather than “installing” it. The project showed the difference between designing surfaces for specific outcomes and working for a unique form of public engagement—for me that makes design and landscape architecture seem so much broader with possibility. Urban@UW: What does the site look like now? Britton: Well, all of the plants continue to grow in. The pearly everlasting is starting to bloom, joining the red clover and sow thistle. Only the sandbags remain on site from the installation. The site is empty, maybe even a bit lonesome. But to me it looks more familiar than it did before, and I hope that others are having the same impression.

Urban@UW: What’s next for you? Britton: I would love to work on another fallow site. One of the lessons learned from Site 1121 was how to better engage people in their visit to the site, and to record their responses, critiques, and feedback. I am researching ways to set up a sort of open-source digital archive for each site that people can visit and interact with to extend the conversations. I think it has a lot of potential not only for designing site-specific installations in land banked sites in the city, but also for a involved community design process. Urban@UW: Reflecting back on your education and what’s inspired you—what would you suggest people read? Britton: I would say Delta Primer: A Field Guide to the California Delta, by Jane Wolff. It’s beautiful. The quality of the research and clarity of the sublime hand drawings are enough for anybody to be interested in this book. But for landscape architects, this book reminds us the rules of the game are never fixed.

Written by Andrew Prindle, Urban@UW Communications Coordinator