Published on April 7, 2021

Many approaches to measuring and supporting city-wide mobility lack the level of detail required to truly understand how pedestrians navigate the urban landscape, not to mention the quality of their journey. Transit apps can direct someone to the nearest bus stop, but they may not account for obstacles or terrain on the way to their destination. Neighborhood walkability scores that measure proximity to amenities like grocery stores and restaurants “as the crow flies” are useful if traveling by jetpack, but they are of limited benefit on the ground. Even metrics designed to assist city planners in complying with legal requirements such as the Americans with Disabilities Act are merely a floor for addressing the needs of a broad base of users — a floor that often fails to account for a wide range of mobility concerns shared by portions of the populace.

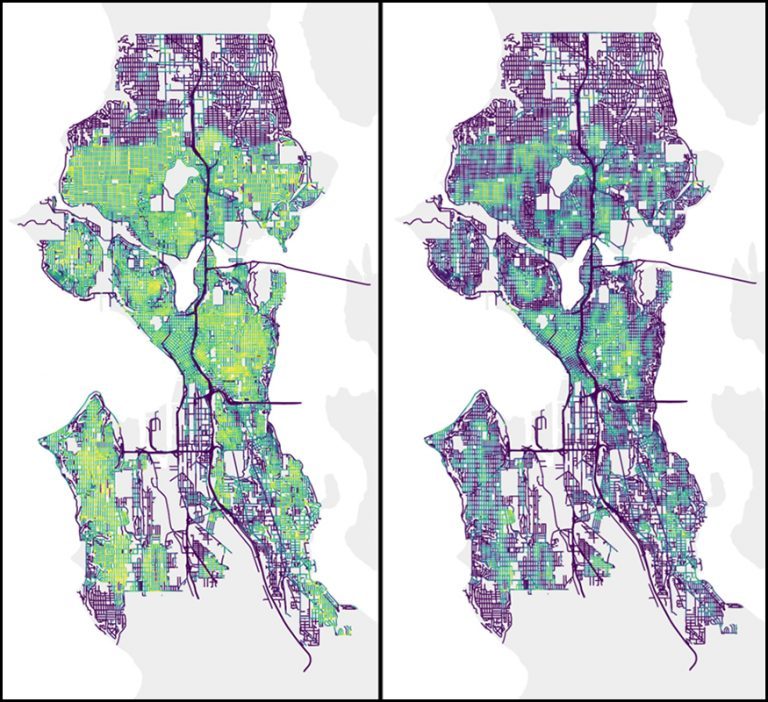

Now, thanks to the Allen School’s Taskar Center for Accessible Technology, our ability to envision urban accessibility is taking a significant turn. In a paper recently published in the journal PLOS ONE, Allen School postdoc and lead author Nicholas Bolten and Taskar Center director Anat Caspi propose a framework for modeling how people with varying needs and preferences navigate the urban environment. The framework — personalized pedestrian network analysis, or PPNA — offers up a roadmap for city planners, transit agencies, policy makers, and researchers to apply rich, user-centric data to city-scale mobility questions to reflect diverse pedestrian experiences. The team’s work also opens up new avenues of exploration at the intersection of mobility, demographics, and socioeconomic status that shape people’s daily lives.

“Too often, we think about environments and infrastructure separately from the people who use them,” explained Caspi. “It’s also the case that conventional measures of pedestrian access are derived from an auto-centric perspective. But whereas cars are largely homogeneous in their interactions with the environment, humans are not. So what we tend to get is a high-level picture of pedestrian access that doesn’t adequately capture the needs of diverse users or reflect the full range of their experiences. PPNA offers a new approach to pedestrian network modeling that reflects how humans actually interact with the environment and is a more accurate depiction of how people move from point A to point B.”

Continue reading at Allen School News.

Originally written for the Paul G. Allen School News.